Sezione Locale della Società Psicoanalitica Italiana

Sezione Locale della Società Psicoanalitica Italiana

di Maja Dobranić

Sarajevo is called the Jerusalem of Europe. Within the space of 500 metres, there (is) ARE the cathedral, the oldest Orthodox seminary, the Bey mosque and the Jewish temple. It was a prosperous place with wide views. Nevertheless, the siege of Sarajevo lasted 1425 days.

AS A WITNESS

Sarajevo was founded during THE Turkish rule. It is located in a valley surrounded by hills and mountains. It’s a rich city in water resources, so traditionally one of its symbols were public fountains with drinking water. There were gates at the entrance to the city. At the gates, one used to be provided with passes to enter the city as to know exactly when a traveller had to leave.

The city then changed, it grew with Bosnia and Herzegovina. When Bosnia and Herzegovina became part of Yugoslavia, Sarajevo happened to be at the centre, like a heart.

The mountains gave us the opportunity to be the organisers of the 1984 Winter Olympics.

We were Yugoslavia and Yugoslavia was us. There were no neighbours, we were all united as brothers.

Sarajevo was perceived as young and it was the golden age of modern Sarajevo when the ‘New Primitives’ movement was born. It was composed of young people in their twenties, who were inclined to humour , lovers of music, art and so on. They were THE living symbols of Sarajevo. Young people were divided into “Raja (the popular)” – they were recognised, respected and esteemed throughout Yugoslavia – and “Papci (Schmuck)”. Humour was a specific characteristic of the city. Money was not the centre of everything and social stratification was frowned upon. Sarajevo was above all multi-ethnic, so that religion was not so important. So much for the romanticization of Sarajevo, youngsters, youth, brotherhood and unity, life.

In a referendum on 1 March 1992, Bosnia and Herzegovina were declared an independent state and left the federation called the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. In a referendum, 64% of the voters voted for independence.

The following Monday, we were expected to go about our daily business but the city had already been surrounded and the streets filled with barricades. On 5 April 1992, there were anti-war demonstrations. The first victims of the siege were there. Ironically, the beginning of the siege of Sarajevo was just one day before 6 April, the day Sarajevo was liberated from the occupiers in World War II.

During the siege, 11,541 citizens of Sarajevo were killed, including 1,601 children, four fifths of whom died in the first two years. The city remained completely isolated, hermetically sealed, until the rescue tunnel was dug. There was no electricity or water and all links to the world were cut off.

It is important to remember that the UN had imposed an arms embargo on Bosnia and Herzegovina, including Sarajevo. Before the siege, everyone had to hand in their weapons at the request of the Yugoslav National Army (JNA), which was the aggressor. So our hands were tied.

PSYCHOANALYST AND VICTIM

During the Turkish rule, the hills served as borders and protection, people could enter the gates where they were taught the city rules and the city structure was kept safe.

In the Golden Age, the ‘raja’ of Sarajevo was the one who set the rules and was the one who enforced them. They were centred on the authentic, respected tradition and centred on the idea of brotherhood and unity – a popular slogan that was part of every speech throughout Yugoslavia. With a constant touch of humour (which was specific, recognisable and sharp) they always managed to make a criticism, make a suggestion or remind that the rules had to be followed. And when it was more aggressive, it was still understandable and effective. It was a warm form of communication, offering intimacy and a kind of community, evoking a feeling of equality.

During the 1990s, the tradition was collapsing under the attacks of the rising politic parties. Myths were used, ghosts were conjured up, history was demonised and distorted: manipulation was at its peak when nationalist parties won. Completely new and unknown rules were introduced and were in opposition with brotherhood and unity. There was a regression towards a symbiosis with one’s own nationality.

On the other hand – it is now clear to us – the exaltation of brotherhood and unity was the result of fantasy, romanticism and idealisation, which blinded us to reality and we paid dearly for it.

The first reaction was (one of) A shock.

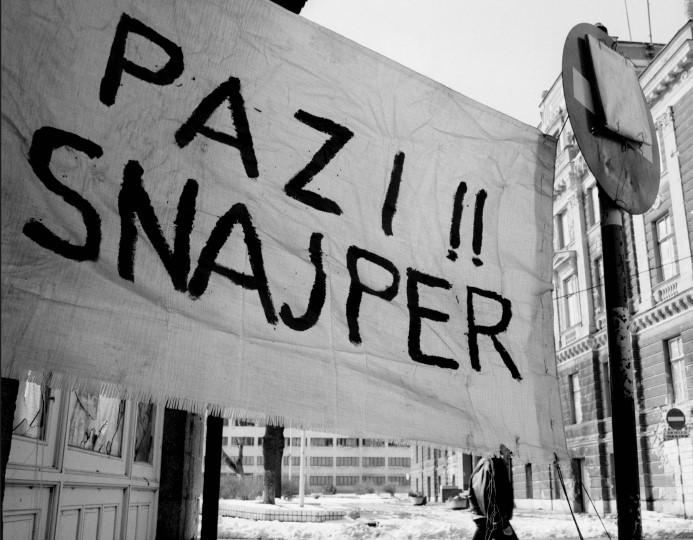

Many flats were abandoned and our friends left. We didn’t know that their departure was a sinister sign and they didn’t know that they wouldn’t be coming back anytime soon. Sarajevo found itself surrounded. The hills that once represented the boundaries and protection of the city were now places from which evil lurked. In order to do as much damage as possible, they were shooting at us from a height and A distance that in some places was measured in a few dozen metres, with weapons used from what had been the world’s fifth largest military force.

The social division, based on the narcissism of small differences, had begun long before, confirming Freud’s words: ‘It is the small differences in otherwise similar peoples that form the basis of their mutual hostile feelings’.

We are all descendants of the Illyrians, we speak the same language, nuanced only in different dialects, we look the same. The differences in religion became a symbol that exaggerated the smallest differences and finally the site of narcissistic insult. People left the city and demolished it in order to adhere to religion.

What Freud says about the narcissism of small differences is that we actually insert unwanted parts of ourselves into others by projective identification and attack them. Thus, small differences divided us into victims and aggressors. The war was so brutal that civilisation was expelled from our lives. We were not ready for such an unthinkable regression: the disbelief and shock were such that for a long time we could not adapt to the events that were happening to us.

Yet, the embargo, the hermetic confinement, the trapping of women and children inside Sarajevo, ended up creating the condition that Machiavelli, in the “Prince”, warned the conqueror to avoid: because when you push a mouse into a corner with no possibility of escape, it will attack.

The urge to survive unleashed all capacities and mobilised all reserves. We experienced first-hand that when we think we have nothing left, we are wrong. You cannot die so easily.

Relationships with neighbours were strengthened, a lot of creativity was used to overcome the problems of A broken glass, damaged roofs, no heating or lighting, recipes for cooking in situations of severe food rationing. Adaptability played a significant role. Undoubtedly, pathological greed also appeared, whereby the smugglers sold a kilo of sugar for 100 KM (about 50 euros). But beyond all that misery and destruction, it must be understood that only enormous inventiveness and the will to live could give the people under siege a chance to survive.

The dead would be buried overnight. Darkness was used as protection because there was no electricity in the city. It was known that gathering more people in one place meant a potential massacre: thus happened Markale one, Markale two, the bread line in Ferhadija, the massacre in Dobrinja, the massacres in the water line. What is absurd, if one stops to think about it today, is that in spite of everything there were theatre plays, concerts, cafés, schools and universities. We tried to live normally in abnormal conditions, that is, we behaved abnormally in abnormal conditions in order to remain normal.

THE PAST HAS NOT PASSED WITHOUT LEAVING A TRACE IN US

24 February 2022, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

5 April 1992, occupation of Sarajevo.

The feelings are the same: shock, fear, disbelief, impossibility of mentalisation. There is a smell of ’92: we buy flour, oil, fuel without any deep understanding or logical explanation. There is mass hysteria. The normal situation becomes extraordinary and life is more difficult because, for example, it is suddenly difficult to find flour for everyday life.

Exhausted by the struggle for survival, we find it difficult to get out of the regression we had to go through to survive.

It seems to me that the Russian invasion of Ukraine has reduced the hostility of our brothers in unity (citizens of Serbia and Croatia), now neighbours. Did empathy return when we all found ourselves in the same position? Did the common similarities in the interest of survival become more important than the differences?

However, the situation is such that we find ourselves functioning with a schizo-paranoid stance, and we run away from the fantasy, listening to reality with suspicion. It is important to integrate the trauma and not leave it isolated. Through processing and awareness, we begin to question it. We control it so that it does not dominate us. We learn from common and personal experience and so we grow.

I use the traumatic experience to approach patients, to help them begin to find the right words for their experiences, to empathise with them to help them mentalise as they help me mentalise, and this is what brings relief to all of us.

Being a storyteller from the position of a victim, a witness and a psychoanalyst was difficult because one role compromised another. I was inclined to put aside the role of the victim, to fill this text with facts which were cold, impersonal, distant. I would have never preferred to write about Sarajevo, about the siege of Sarajevo, about the aggression against Bosnia. I would like to talk about all this while looking at the faces of the listeners, because for me it is important to get an echo and not to keep the words hanging in the air.

And finally:

Why does a fox never catch a rabbit? Because the fox runs for lunch and the rabbit runs for life.

Maja Dobranić, Sarajevo

International Psychoanalytical Association

Società Psicoanalitica Croata

Condividi questa pagina:

Centro Veneto di Psicoanalisi

Vicolo dei Conti 14

35122 Padova

Tel. 049 659711

P.I. 03323130280