Sezione Locale della Società Psicoanalitica Italiana

Sezione Locale della Società Psicoanalitica Italiana

By Elisabetta Marchiori – Italian Psychoanalytic Society

This paper has been presented at the 53th Congress of Internazionale dell’International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA) in Cartagena (Colombia)- 26-29 July 2023

Introduction

From July 26-29, 2023, the 53rd congress of the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA) with the particularly evocative title Mind in the Line of Fire was held in Cartagena, a wonderful Colombian city full of life, song and color.

During the Saturday morning I was a speaker at the panel organized by IPA in Culture Commettee, whose chair is Cordelia Schmidt-Hellerau (Swiss Psychoanalytic Society)

entitled Resistance in the Face of Fire. Together with colleagues Andreas Mittermayr (Vienna Psychoanalytic Society,) Claudia Antonelli (Brazilian Psychoanalytic Society of Campinas), Valeria Ricchieri (Argentine Psychoanalytic Association), Barbara Stimmel (American Psychoanalytic Association), and Johanna Velt (Paris Psychoanalytic Society) we had the opportunity to show how the creativity — with which artists, writers, musicians, and filmmakers respond to danger, pain, and dramatic life events — can become a form of resistance, transforming the experience of death and destruction into the different languages of culture and art.

The following is my contribution focused on cinema and one film in particular, an extreme summary of a paper published by IPA in the bilingual book Mind in the Line of Fire / Mente en la Línea de Fuego: Psychoanalytic voices to the challenges of our times / Voces psicoanalíticas ante los retos de nuestro tiempo, and edited by Cordelia Schmidt-Hellerau, & Mira Erlich-Ginor.

Reflection: a Film about the Resistance of the Mind in the Line of Fire

By Elisabetta Marchiori – Italian Psychoanalytic Society

“Cinema’s mission is to direct us

toward the aspects of the world that we didn’t see.“

(Eric Rohmer)

It is certainly not the role of war cinema to make the audience “understand” war, nor to heal ignorance of history. However, the power of the images flowing on the screen in a darkened movie theater prevents us from closing our eyes to the “pain of others” (Sontag, 2003). Cinema can become a form of resistance, enhancing the ability to think in the face of the horrors of war, compared to the incessant stream of the images of atrocities broadcast nonstop by televisions and spread virally by social networks.

Regardless of the ethical value of such images, they risk creating habit, detachment and apathy, causing us to lose our sense of compassion for people who suffer.

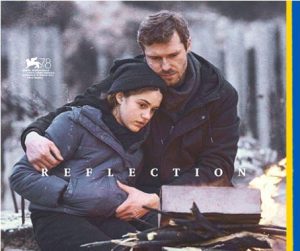

In the film “Reflection” (2021) by Ukrainian director Valentyn Vasyanovych (presented at 78th Venice International Film Festival), the scenario is the Donbass war, which began in 2014 as the prelude to the so-called “special operation”, the invasion war launched in February 2022.

On July 2023 not only had the war in the Ukraine not ceased, but it seems to have infected the world, renewing conflicts that had long been dormant: war was once again becoming an element of unification of the society that produces consensus.

The title is already very evocative: on the one hand it refers to the “reflections” of the war on people’s lives and psyches, on the other it offers difficult and traumatic questions to the audience, soliciting openings of thought and “reflections” about what is inhuman and what is deeply human in war.

This film shows the strength of creativity and repair and stands as a front of resistance to the force of destructiveness and alienation, investigating the possibility of making sense of what seems meaningless, in a kind of psychoanalytic elaboration.

The main characters are a 10-year-old girl and her two fathers, fraternal friends, who both left for the front: the biological father, who survives, and the stepfather, who loses his life.

Frame after frame, “reflection” after “reflection”, each character and each object questioned by the camera releases a meaning; each image reflects something else, and makes us wonder what atrocities, what deaths, what sufferings we are not shown.

This film freezes the time of war in an infinite and exhausting present, obliterating and conditioning people’s lives, and places it in the depth of the human being where the inhuman takes the place of the human.

The sequences in which there are large windows recur throughout the film, both as a symbol of the distance between the observer and the observed and as a symbol of the psychic resistance of the “mind in the line of fire”, in a protective and creative sense. And then there is the broken glass, which refers to a risk, namely that the individual, in the face of horror, not only activates denial, but also more archaic defense mechanisms such as dissociation and fragmentation.

The first part of the film is a depiction of war: the scenes follow one another at a slow but inexorably pressing rhythm, full of silences and noises, sounds, shouts and few words; there is no music. The shots are fixed, the images freeze in paintings of cold and dark colors, to expose scourged bodies; the spaces are the claustrophobic ones of detention and torture cells or outdoors, in desolate agoraphobic “non-places” (Augè, 1992).

The narration, in the second part of the film, is more fluid; the war is not displayed, but its consequences can be seen, in the protagonists’ bodies stiffened by the pain and in the sadness of their looks, which come alive again in mutual contact.

The shattered windows disappear, but not the reflections: the story develops around the imprint of the body of a pigeon that smashed violently into a window — deceived by the reflection of the sky — on to the surviving father’s house, in the presence of his daughter.

That “beautiful and terrifying”[1] winged form is the “reflection” of the trauma.

The death of the pigeon, which mirrors that of the little girl’s stepfather, transforms the film into a story about the relationship between a father and daughter, involved together in grieving the loss of a loved one.

In the end, as we shall see, there are still other “reflections,” those of the sound of the footsteps of our beloved ones — those present and alive, as well as those absent and dead. They can be recognized through attentive and authentic emotional listening to the “good enough” relationships (Winnicott, 1971), consolidated in pain and allowing the psychic life to resist and evolve.

Now I’d like to show you some sequences from the film which illustrate what I am talking about.

Augé M. (1992). Non-places: introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity. Le Verso Books, Le Seuil.

Sontag S. (2003) Regarding the Pain of Others. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York.

[1] https://www.labiennale.org/en/cinema/2021/lineup/venezia-78-competition/vidblysk-reflection

Condividi questa pagina:

Centro Veneto di Psicoanalisi

Vicolo dei Conti 14

35122 Padova

Tel. 049 659711

P.I. 03323130280